Lingering consumer anger over high prices is hurting governments in advanced economies even though inflation is subsiding to normal levels, as a once-in-a-generation surge in costs leaves a toxic legacy for incumbent politicians.

Discontent over the economy was a key motivator for Republican voters in last week’s US election, exit polling suggested — contributing to vice-president Kamala Harris’s defeat at the hands of Donald Trump.

Incumbents in countries including the UK and Japan have also suffered in elections this year, partly because of anger at high living costs.

Polling suggests the legacy of inflation will also play a role in national elections next year, including in Germany and Canada.

“It takes time for a spike in prices to work its way through the electoral digestive system,” said Robert Ford, professor of political science at the University of Manchester. “Inflation is really only over for normal voters when they get used to the new price levels . . . We have not arrived at that point yet.”

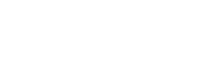

The average inflation rate across the OECD group of rich countries fell to its lowest level since the summer of 2021 in September, the most recent month for which a full set of data is available. It is now hovering around central banks’ 2 per cent target in more than half of OECD members, including the UK, Italy, France and Canada.

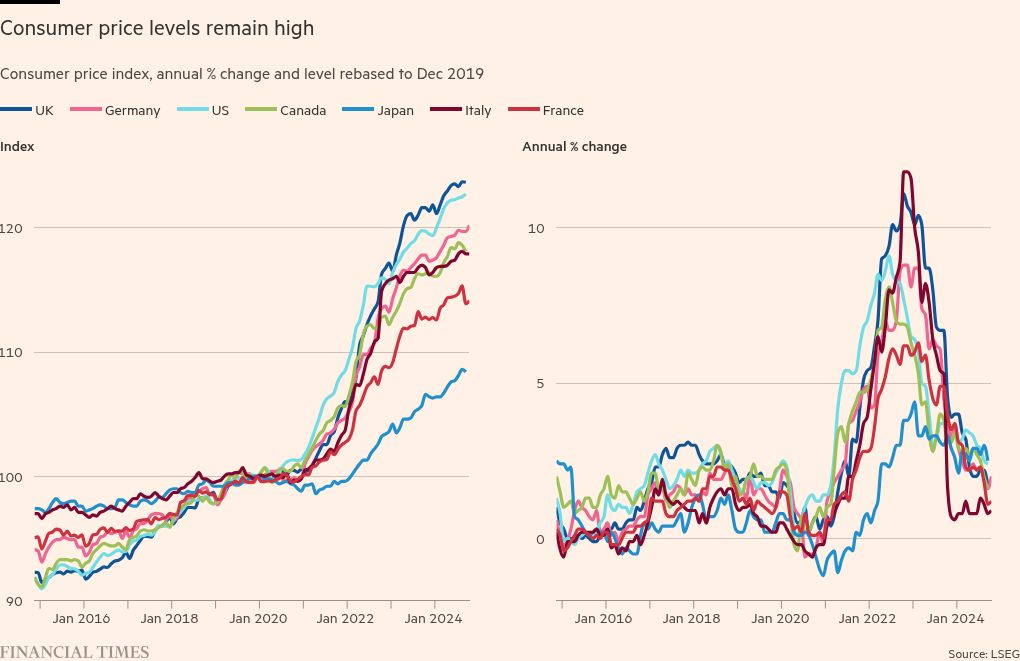

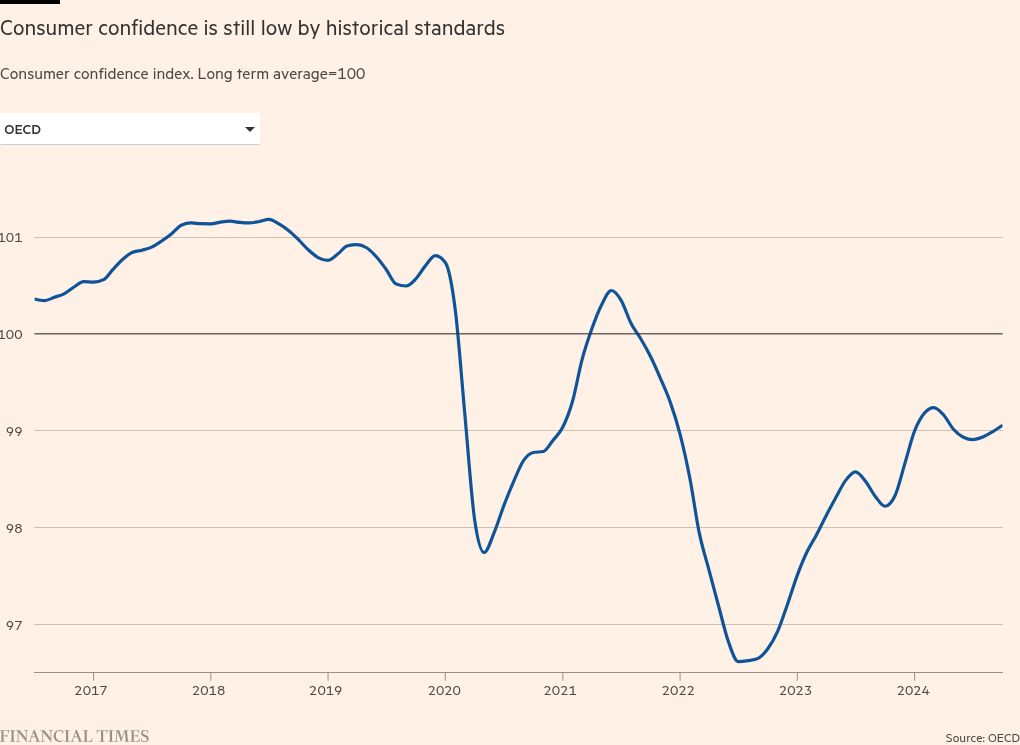

Despite this, consumer confidence remains 1.7 per cent below pre-pandemic levels across the group, reflecting discontent over high living costs. While wages are now growing at a faster pace than prices, real incomes in many large economies have only just surpassed pre-Covid levels.

Average price levels across the OECD were approximately 30 per cent higher in September 2024 than they were in December 2019, before Covid’s emergence triggered a series of shocks and policy responses which, when combined with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, fuelled the inflationary surge.

“[Consumers] look at how much they spend on their utility bill or their weekly food shop and conclude that these costs aren’t going down, so the cost of living crisis is still going on,” said Paul Dales, economist at consultancy Capital Economics.

Food prices are about 50 per cent higher than in December 2019, with average hourly wage growth failing to keep up in about half of the OECD countries.

“Consumers (and voters) tend to remember price levels,” said Paul Donovan, economist at UBS. He said in a note that older prices stick in people’s minds for 18 months or more and higher prices are considered “unfair”.

Isabella Weber, professor of economics at University of Massachusetts Amherst, said historical research shows that “bursts of inflation can destabilise” whole societies and political systems.

She said the latest episode has been particularly dangerous as developed economies have not been used to high inflation since the 1970s and the rise in prices was mainly driven by essential goods such as food, housing, energy and transportation.

As working people went to bed hungry, “they lost trust in the system and got very angry at the state”, she said.

In Germany, which is heading towards a snap election early next year after Chancellor Olaf Scholz abandoned his tripartite coalition, the main political winners of the inflationary surge are anti-establishment parties on the left and right.

The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) and hard-left Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) are set to win a quarter of all votes, a level of support for extremists that is unprecedented since the 1920s.

While 44 per cent of Germans are concerned that they may be unable to afford their current lifestyle, the figure rises to 75 per cent and 77 per cent for supporters of the BSW and AfD respectively, according to a survey by Infratest Dimap on behalf of public broadcaster ARD published last month.

In Canada, where federal elections will take place next year, Conservative opposition leader Pierre Poilievre has used the cost of living crisis as a weapon against Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

While inflation is now just 1.6 per cent, his tactic appears to be working. About 34 per cent of Canadians described rising costs as their top priority in a Leger poll in September.

Only one in five Canadians expect their finances to improve over the next 12 months, according to a separate Angus Reid poll.

Even where real wages have surpassed pre-pandemic levels, elevated prices are still a hot political topic.

About nine in 10 Britons interviewed in September said the cost of living crisis was “the most important issue facing the UK”, despite headline inflation dropping to a three-year low of 1.7 per cent.

Rachel Reeves, the Labour chancellor, said on Thursday that she was “under no illusion about the scale of the challenge facing households”.

Sebastian Dullien, research director of Düsseldorf-based Macroeconomic Policy Institute, a think-tank funded by German trade unions, said diverging explanations for rising prices and wages had also fuelled discontent.

Workers attributed recent gains in income to their own hard work, while higher prices were down to external forces beyond their influence.

“Many people appear to perceive a sudden rise in cost of living as unfair and fear a loss of control over their lives,” said Dullien.

Additional reporting by Jude Webber in Dublin

Data visualisation by Valentina Romei and Steven Bernard