“Gold continues to be one of the most important reserve assets globally, as evidenced by the significant purchases of gold by central banks in recent years.”

– Hungarian central bank, September 2024

As we enter the final stretch of 2024 with the international gold price having made continual new highs during the last 8 months, it’s encouraging to see that central banks, on a collective basis, are still large net buyers of physical gold for their monetary gold reserves.

According to the World Gold Council’s just released Gold Demand Trend (GDT) report for the third quarter 2024, central banks (and other official sector institutions) added a net 694 tonnes of gold to their monetary gold reserves during the first 9 months of 2024. This comprises net buying of 305 tonnes of gold in Q1, 203 tonnes in Q2, and 186 tonnes in Q3.

Based on World Gold Council data (which is collected by precious metals consultancy Metals Focus), January – September 2024 central bank gold purchases are below the January – September 2023 period (when central banks added a net 833 tonnes of gold ), but on a par with the first 9 months of 2022 (when central banks bought a combined 700 tonnes of gold).

Recalling that 2022 was a record year for central bank gold buying (with central banks net buying 1082 tonnes of gold), and 2023 was not far off that (with central banks net buying 1049 tonnes), then 2024 is set to be a respectable year also, independent of what buying might or might not occur in the fourth quarter of 2024, and shows that the investment rationale of central banks buying gold – store of value, safe haven, no counterparty risk, no sanctions risk, diversification benefits – are still intact.

First a few caveats about World Gold Council (WGC) central bank gold buying data – It comprises both reported gold buying by central banks (which the central banks report to the IMF’s International Financial Statistics database as well as publish on their own websites as international reserves data), but also comprises unreported gold buying by central banks (which the WGC makes an estimate of based on “market feedback” and which it describes as “confidential information regarding unrecorded sales and purchases.”

This “unreported gold buying” component is also far bigger than the ‘reported’ component, with for example, the World Gold Council claiming that central bank and official sector institution gold demand was 507.4 tonnes in the first half of 2024, while only being able to explain 124 tonnes of this total as reported central bank gold buying over the same period. So that’s 383.4 tonnes of central bank gold buying ‘not reported’, but which the World Gold Council claims to know about.

We therefore have an absurdly unscientific situation where 75.5% of claimed central bank gold buying during H1 2024 is from unidentified central bank buyers, and only 24.4% is from central bank buyers who have publicly divulged their purchases. It is also the case that since the World Gold Council won’t reveal the information it claims to know about, then no one can scientifically verify its correctness, nor can anyone refute it.

This situation is reminiscent of the now well-known quote from Donald Rumsfeld:

“There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.“

In this case, the “known knowns” are the reported gold buying transactions of central banks, the “known unknowns” are the unreported buying transactions, and the “unknown unknowns” is any central bank gold buying which may have occurred totally under the radar unbeknownst to anyone except the buying and selling parties.

This lack of transparency therefore makes it challenging for anyone outside of World Gold Council / Metals Focus to assess the veracity of their central bank gold demand claims, and the market is left to speculate on the identities of the unidentified buying entities. While the unidentified buyers probably include countries such as China, Saudi Arabia, and Russia, as well as various sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), it would be nice to have this in writing.

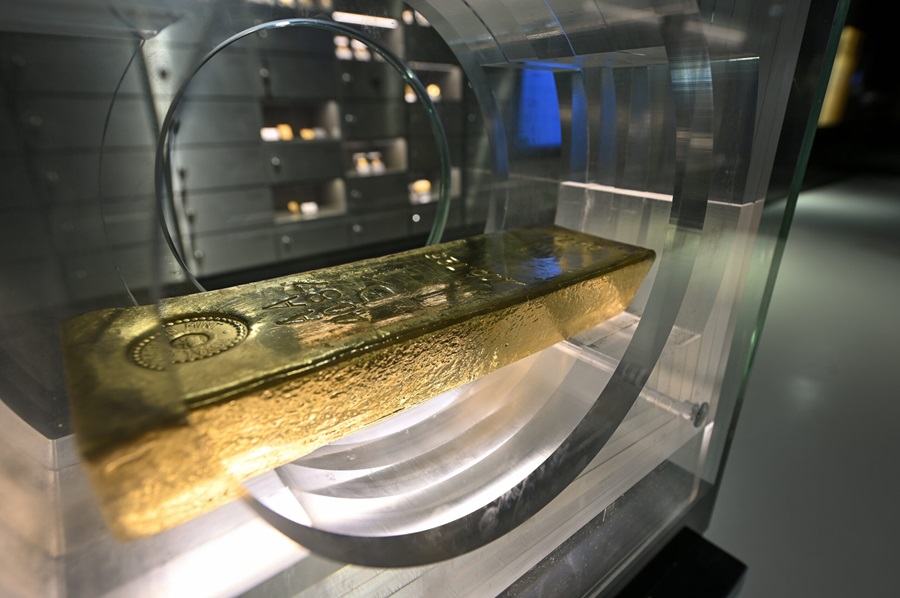

However, given that this is not possible, we can still look at the “reported buyers”. And they are as follows:

On a year to date basis, Poland’s central bank is the largest reported gold buyer, buying 61.2 tonnes of gold so far in 2024, including in September. In second place is the central bank of Turkey, which in the first 8 months of 2024 up until August, added 51.5 tonnes of gold to its reserves. In third place is India’s central bank, which added 50 tonnes of gold to its reserves between January and September.

And in fourth place is the Chinese central bank, which even though it only officially added gold to its reserves between January and April 2024, still claims to have added 28.9 tonnes to its reserves over that time.

And a special mention for the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan (SOFAZ), which although not a central bank, is Azerbaijan’s sovereign wealth fund (SWF), and this SOFAZ purchased a cumulative 25.2 tonnes of gold during the first 9 months of 2024.

The Visegrad Group – Central European Cooperation

We first turn our attention to a group of central banks in Central Europe, which are actively building their monetary gold reserves – the central banks of Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. It’s arguable whether these countries are classified as being emerging markets or developed markets, but some classifications put them in the emerging market category, including the World Gold Council.

It’s intriguing that the central banks of three of the four Visegrad Group members – Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic – are all currently increasing their gold reserves simultaneously, and that all three have cited that gold accumulation is a strategic move in response to economic uncertainty, store of value motives, a need for diversification, and because of growing geopolitical risks.

Given that Visegrad Group’s was established to promote cooperation and regional stability, it’s plausible to think that central bank discussions among Visegrad Group members about accumulating gold have already occurred in recent years (since at least 2018) and are probably ongoing. The fact that Poland, Czech and Hungary (while all in the European Union) still all retain their own domestic currencies and none of them are part of the Eurozone, also gives each of these countries huge flexibility and independence in being able to continually purchase monetary gold, unlike their Eurozone counterparts that are slavish to the ECB.

The National Bank of Poland

In 2023, Poland’s central bank, the National Bank of Poland (NBP), made headlines by purchasing exactly 130 tonnes of gold, which it accumulated over a 7 month period from April to November 2023 inclusive, and which made Poland the second largest sovereign buyer of gold last year, behind the Chinese central bank.

Following Poland’s notable gold accumulation of 2023, the Polish central bank has returned to the gold market again this year, buying a total of 61 tonnes of gold over the 6 month period from April to September 2024, of which a sizeable 22 tonnes was in the month of September alone. This now makes Poland the leading central bank gold buyer so far during 2024.

Poland’s gold holdings now total a huge 420 tonnes of gold, with the value of NBP’s monetary gold now representing 16% of the Polish central bank’s total foreign reserves.

In May at a press conference in Warsaw, Adam Glapiński, head of the NBP, explained that the NBP was accumulating gold due to economic uncertainty, saying that:

“We will accumulate huge [amounts of] foreign currency and gold reserves as Poland must be ready for any eventuality – the NBP is prepared.”

It’s worth noting that just over 6 years ago in June 2018, the Polish central bank still ‘only’ held 103 tonnes of gold, a holding which had not increased since 1998, and a holding which ranked the NBP in 34th place in terms of global central bank gold holdings.

Poland then bought 25.7 tonnes of gold in 2018, and another 100 tonnes of gold in 2019, bringing its total monetary gold reserves to 228.6 tonnes. See BullionStar article “Poland Joins Hungary With Huge Gold Purchase & Repatriation” from July 2019. Add in the 130 tonnes bought in 2023 and the 61 tonnes bought so far in 2024, and Poland’s 420 tonnes now rank it in 13th position globally in terms of sovereign gold holders. Quite a jump since 2018.

Which is why Glapiński also commented on Poland’s gold at another press conference in early October where he said:

“Specifically, we now hold 420 tonnes. Poland has thus entered the exclusive club of the world’s largest gold reserve holders.“

Importantly, Poland’s gold buying spree is set to continue, as Glapiński said that the central bank plans to continue buying gold:

“We are aiming for 20 percent of our currency reserves to be in gold. Once we achieve this, we will join the ranks of the world’s top economies.”

Based on Poland’s current foreign exchange reserves, this 20% ratio of gold to total foreign reserves would mean that the NBP is aiming to hold approximately 526 tonnes of gold, which means that the NBP still needs to buy another 106 tonnes of gold.

The Czech National Bank

During 2024, the central bank of the Czech Republic, the Czech National Bank (CNB), has continued the gold buying spree which it started in March 2023, and has now been buying gold for 19 consecutive months.

On top of the 18.7 tonnes of gold accumulated between March and December 2023, the CNB has so far this year purchased another 15.7 tonnes between January and September, for a total purchase of 34.4 tonnes over that 19 month period.

This leaves the Czech National Bank with a respectable 46.4 tonnes of monetary gold reserves in total. However, similar to the Polish central bank, this is not the end of the Czech central bank’s gold accumulation, far from it. That is because CNB governor Aleš Michl indicated in June that he wants to boost the central bank’s gold holdings to 100 tonnes.

This 100 tonnes number has not just been pulled out of the air by Michl. In fact, Aleš Michl, who has a PhD in finance, co-authored a CNB research paper published in September 2023 which examined volatility, expected return and optional asset allocation for the CNB’s foreign exchange and gold portfolio, and which specifically modeled increasing the CNB’s gold holdings to 100 tonnes, and which concluded that:

“if asset prices follow the pattern of the last 20 years, it would be appropriate to increase the share of equities to about 20% of the FX reserve portfolio and to increase the share of gold to up to 100 tons.“

Michl also said in June this year that “the bank’s strategy will be to make gradual purchases and we won’t be trying to time the market”, which explains why the CNB is adopting a ‘dollar cost average’ approach of buying gold each and every month for the last 19 months, and not buying in one chunk all at the same time. See Aleš Michl interview with Bloomberg, dated 19 June 2024, here.

The Hungarian National Bank

Recall that in October 2018, the Hungarian National Bank (known as Magyar Nemzeti Bank (MNB)), only had 3.1 tonnes of gold, but that month purchased a a mammoth 28.4 tonnes of gold in London, bringing its monetary gold holdings to 31.5 tonnes, i.e. a 10-fold increase. The gold bought in October 2018 was also instantly repatriated back to Hungary from London at the time of purchase. See BullionStar article “Hungary Announces 10-Fold Jump in Gold Reserves”.

Following this, the Hungarian central bank raised its gold holdings even further, when it bought a whopping 63 tonnes of gold bars in March 2021, and in doing so tripled its gold holdings from 31.5 tonnes to 94.5 tonnes. See BullionStar article “Hungary Boosts Gold Reserves by 3,000% in Under 3 Years”.

Now after three and a half years, the Hungarian National Bank has gone back into the gold market again this September and boosted its monetary gold holdings even further, from 94.5 tonnes to 110 tonnes by buying 15.5 tonnes.

In a press release at the end of September 2024 announcing the purchase, and titled “The MNB increased Hungary’s gold reserves to a record high level of 110 tonnes”, Hungary’s central bank states that:

“In line with the country’s long-term national and economic strategy objectives, the MNB boosted its gold reserves by more than tenfold to 31.5 tonnes in 2018, and then tripled them to 94.5 tonnes in 2021.

By increasing the current level of gold reserves to 110 tonnes, the MNB continues its process of purchasing gold it began in 2018 to achieve its long-term national strategy goals.”

The press release continues:

“In recent years, the global economic, geopolitical and capital market trends that have contributed to the appreciation of gold, have intensified.

Gold has played a variety of roles in different financial systems throughout history. It is an effective complement to foreign exchange reserves even under normal market conditions.

In times of heightened financial and geopolitical uncertainty and under extreme market circumstances, the role of gold as a safe haven asset and store of value is of particular importance as it can enhance confidence in the country and underpin financial stability.

Because of all these advantages, gold remains one of the most important reserve assets worldwide.”

National Bank of Serbia

Staying for the moment in Central Europe, it’s interesting to examine what is probably the longest ‘dollar cost averaging’ period of a central bank buying gold in recent history, by Serbia’s central bank, the National Bank of Serbia (NBS).

This is because the NBS has consistently bought gold each and every month for 55 months between February 2018 and August 2022, and in that time accumulated 18.6 tonnes.

Following a 13 month break, the National Bank of Serbia then recommenced gold buying in September 2023, adding gold to its reserves in every month for 11 months, most recently with a sizeable 5.3 tonnes purchase in July 2024, which is the largest monthly addition by the Serbs since October 2019 when the central bank bought 9 tonnes of gold.

So far this year, the Serbian central bank has added 6.8 tonnes to its gold reserves, and now claims to hold 46.7 tonnes of monetary gold.

With an increasing share of gold in the NBS external reserves, the National Bank of Serbia says that “FX reserves not only increased, but their structure has improved as well – the quantity, value and share of gold went up notably.”

As of the end of May 2024 (when Serbia held 41.2 tonnes of gold), all of this gold was being held in the NBS vaults in Serbia, which included 13 tonnes of gold repatriated from abroad in 2021 (of which 12 tonnes had been purchased abroad). See National Bank of Serbia website, here.

Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye

The central bank with the second largest reported gold buying total so far in 2024 is the Turkish central bank, which according to IMF data as reported by the World Gold Council, bought a sizeable 55.2 tonnes of gold for its official reserves since January 2024, announcing buying every month between January and September, most recently adding 3.7 tonnes during September.

Note that this relates to Turkey’s official sector gold reserves, which is monetary gold owned by the central bank and the Turkish Treasury combined. After the latest buying, this leaves Turkey with 595.4 tonnes of gold, putting it in 10th place globally in terms of sovereign gold holder rankings.

Reserve Bank of India

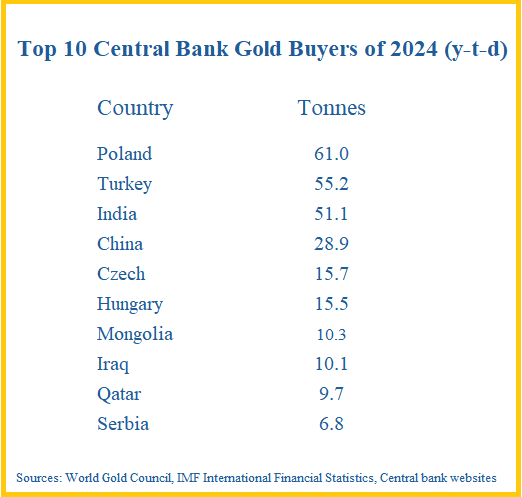

Following the purchase of 16.2 tonnes of gold during 2023, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), India’s central bank, notably accelerated gold purchases during 2024, and announced gold reserve additions for every month between January and September 2024, during which time it added another 51.1 tonnes of gold to its reserves. This leaves the RBI with a substantial 854.7 tonnes of gold.

Notably, the RBI, via its half yearly reports on ‘Management of Foreign Exchange Reserves‘ also announced that between March 2023 and September 2024, it had repatriated more than 200 tonnes of gold from abroad back to the RBI gold vaults in Nagpur, India, all or which, or nearly all of which, was repatriated from the Bank of England in London.

People’s Bank of China

After having ‘officially’ added a mammoth 316 tonnes of gold to its official reserve during an 18 month consecutive period between November 2022 and April 2024, the Chinese State / (People’s Bank of China), via the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), suddenly stopped making such announcements, and therefore hasn’t ‘officially’ added any gold to its monetary gold reserves during the May – September 2024 period.

Having said that, given that China announced a cumulative addition of 28.9 tonnes of gold to its reserves for the January – April 2024 period, these 4 months alone put China among the top central bank gold buyers for 2024, and leave the world’s largest gold player ‘officially’ with 2,264 tonnes of gold.

As readers of this site will be familiar with, China is assumed to be always buying gold but not necessarily announcing additions to its gold reserves, and is also assumed to have far more monetary gold than it admits to having.

For more discussion of China’s gold accumulation strategy, see the recent BullionStar article from May this year titled “Central Bank Gold Buying – Latest Trends and Developments”.

Bank of Russia

Officially, Russia’s central bank, the Bank of Russia announced only minimal gold transaction activity during 2024, with a 3.1 tonnes sale in January, then a 3.1 tonnes purchase in March and another 3.1 tonnes purchase in April, for a net 3.1 tonnes addition.

However, due to ongoing sanctions on Russia by the US/EU/UK/G7 and the freezing of a portion of Russia’s foreign reserve assets by those same entities, it would be strategically logical for the Russian central bank to avoid publicising further accumulation of gold, and also to avoid inviting further sanctions on its ability to buy and trade gold in international markets.

Russia could also be continuing to buy gold from its domestic gold mining companies as it did for many years since the early 2000s (via the network of Russian banks which operate in the Russian gold market and which liaise with domestic gold refineries and domestic gold producers). Therefore, the jury is still out on whether the Russian central bank has been continuing to buy larger quantities of gold during 2024 than it has announced.

Bank of Mongolia

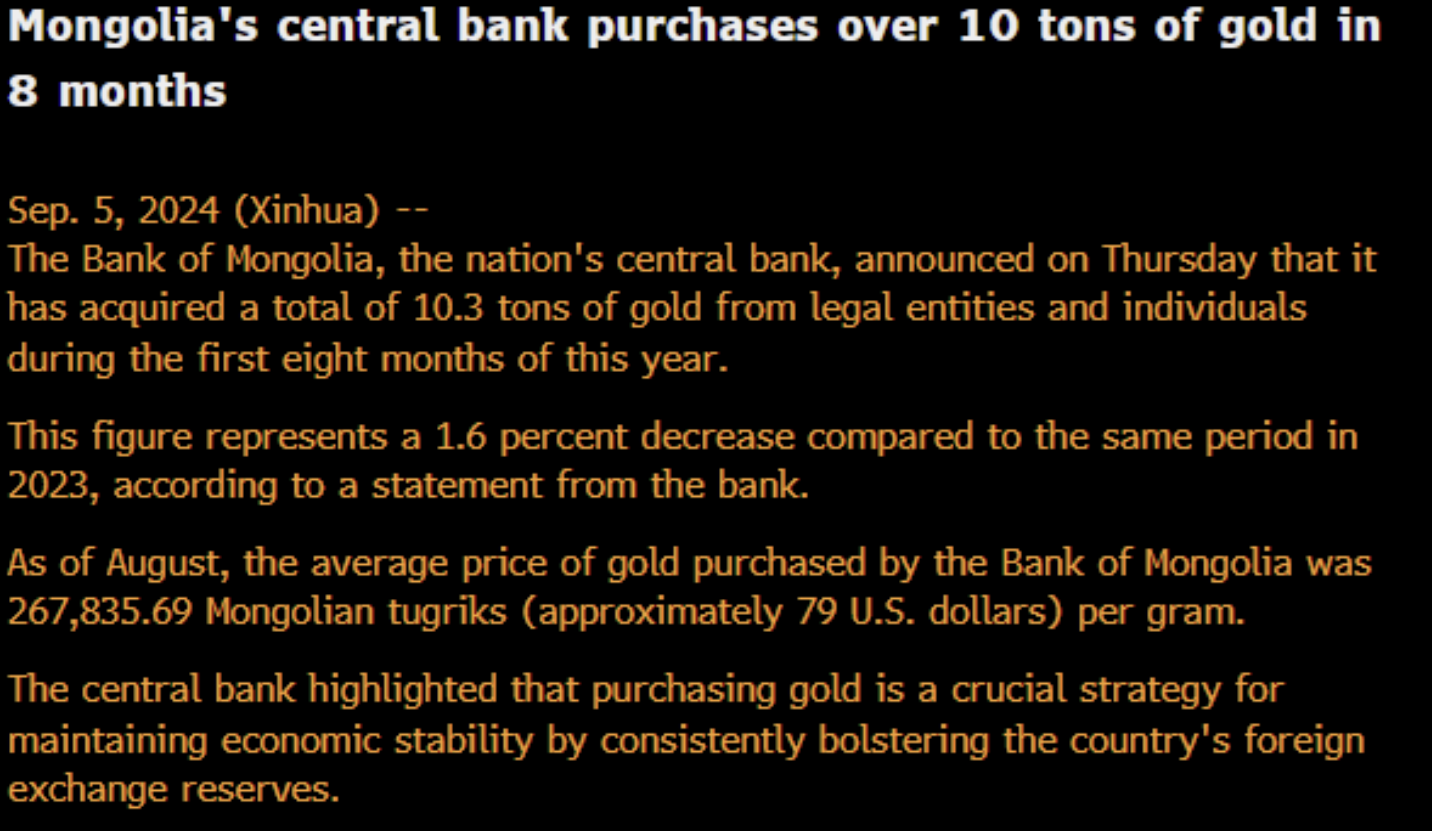

Positioned right between its neighbours China and Russia, Mongolia’s central bank also realises the importance of holding gold in its external reserves. To this end, the Bank of Mongolia, Mongolia’s central bank, has already bought 10.3 tonnes of gold so far in 2024, between January and August.

This gold was purchased from domestic “legal entities and individuals”. According to Chinese news network Xinhua, Mongolia’s central bank “highlighted that purchasing gold is a crucial strategy for maintaining economic stability by consistently bolstering the country’s foreign exchange reserves.”

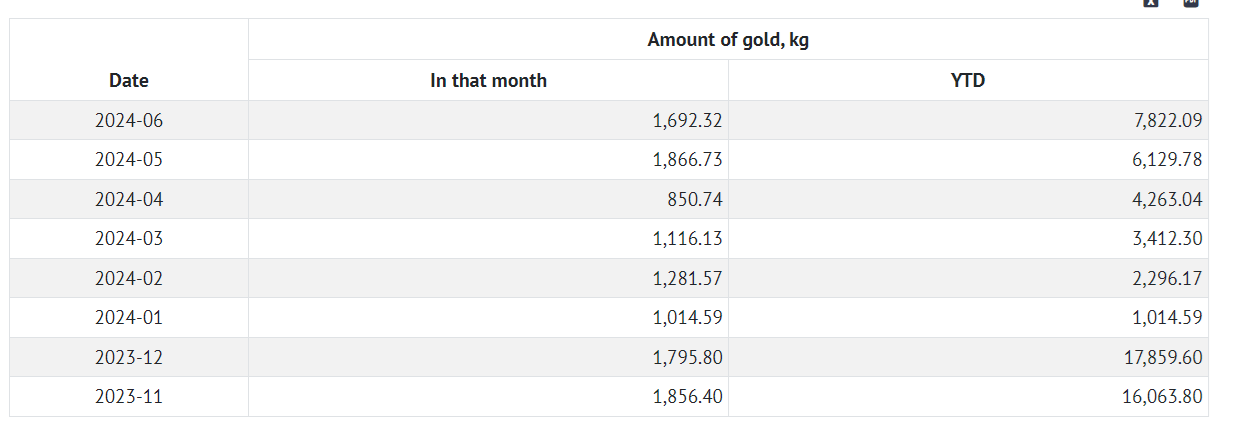

The most recent monthly gold purchase by the Bank of Mongolia was in August when the bank bought 0.93 tonnes. Since the Bank of Mongolia does not report its gold buying to the IMF database, none of Mongolia’s gold purchases are included in the World’s Gold Council’s calculations of central bank gold transactions, however, they can be seen on the Mongolian central bank’s own website, on a page dedicated to its gold purchases, which can be seen here.

Interestingly, a session in the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) 2024 annual conference held in Miami in mid October, titled “Why Gold Still Matters for Central Banks” featured head of the financial markets department at the Central Bank of Mongolia, Enkhjin Atarbaatar, in which he stated that “the importance of gold as a secure asset is increasing for Mongolian reserves”.

Central Bank of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan in Central Asia is an unusual case as regards central bank gold ownership, since even though its central bank, the Central Bank of Uzbekistan, holds huge monetary gold reserves, which in September according to IMF data totalled 12.02 million troy ounces or 373.86 tonnes, the central bank is constantly a net seller or a net buyer of gold each month, but the overall set of transactions has not, in the recent past, boosted its gold reserves significantly.

For example, over the first nine months of 2024, the Central Bank of Uzbekistan’s monetary gold increased by 9 tonnes in January, then fell by 11.8 tonnes in February, fell again by 10.9 tonnes in March, fell again by 1.2 tonnes in April and by another 0.6 tonnes in May, then increased by 9.3 tonnes in June, increased by another 9.6 tonnes in July, fell by 0.9 tonnes over August and September, to give a net increase over the January – September period of just 2.5 tonnes.

This seemingly haphazard set of gold transactions by the central bank makes more sense when you release that gold is one of Ukbekistan’s largest exports, with, for example, Uzbekistan exporting $2.66 billion of gold in Q1 2024, which accounted for 41.7% of the country’s total exports. According to the 2024 US Geological Survey for gold, Uzbekistan mining produced 100 tonnes of gold in 2023.

As Mamarizo Nurmuratov, head of the Central Bank of Uzbekistan explained in February of this year:

“In the near future, Uzbekistan’s producers will be able to sell gold directly on the world market. Currently, the Central Bank of Uzbekistan buys gold inside the country in sums and sells them for dollars on the foreign market.“

The gold transactions of the central bank are thus reflecting the central bank buying gold from local producers, and then selling gold at times on the international market to raise foreign exchange.

Latest data from the Central Bank of Uzbekistan’s international reserves report, as of 1 October 2024, shows that the bank still holds 12.0 million troy ounces of monetary gold on its balance sheet (no change from September). Interestingly, as well as monetary gold of 12 mn ozs, the international reserves report shows that the central bank holds another 9.9 mn ozs of gold (307.92 tonnes) but that gold is classified as “gold not included in official reserve assets”. Adding the two categories together means that Uzbekistan’s central bank controls a huge 681.8 tonnes of gold, something that no one seems to have ever highlighted in the Western financial media.

National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic

Directly east of Uzbekistan, in neighbouring Kyrgyzstan, the country’s central bank, the National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic, has also earned a reputation for frequently transacting in gold, and has added 4.3 tonnes to its gold reserves during the first half of 2024.

This followed the addition of a net 5.2 tonnes of gold to the bank’s reserves during 2023. Overall, Kysgyzstan’s central bank now holds 830,000 ozs of gold, or 25.8 tonnes.

Central Bank of Iraq

Turning attention now from Central Asia to the Middle East, after buying a net 12.3 tonnes of gold between May and October 2023, the Central Bank of Iraq has kept its gold buying momentum going, and according to the World Gold Council data, the Iraqis added another 10 tonnes of gold between February and July 2024 (3.1 tonnes in February, 3.1 tonnes in May, 2.8 tonnes in June, and 1 tonne in July).

According to Bloomberg in early February, the director of the Central Bank of Iraq’s investment department, Mazin Sabah, said that the bank bought nearly 2.3 tonnes of gold in January. Since this is not shown by World Gold Council data, it looks like these purchases were added into February’s figures.

Interestingly, at that time in early February, Sabah had also telegraphed that Iraq would buy more gold during 2024, when he said that ‘future purchases will take Iraq’s holdings to a record.”

This turned out to be the case, since as of October 2024, Iraq’s central bank now claims to hold 152.6 tonnes of monetary gold reserves, the highest on record.

Qatar Central Bank

After having accumulated a net 34.5 tonnes of gold over the 6 year period from 2016 – 2021, Qatar’s Central Bank (QCB) upped the ante in 2022 by buying another 35 tonnes of gold in 2022, all of it before the 2022 FIFA World Cup which the country hosted between November and December 2022.

Whether the timing of the Qatari’s 2022 gold purchases and the Qatari World Cup was a coincidence, we will never know, but in recent years, the gold buying transaction of the Qatar central bank have put it front and centre on the radar among the world’s central banks and allowed the Doha based institution to rise up through the ranks of sovereign gold holders. See BullionStar article “Qatar Ramps Up Gold Reserves as World Cup Approaches” from September 2022.

Qatar’s gold buying spree continued into 2023 with the QCB scooping up another 9.1 tonnes of gold between June and December 2023, and then another 7.8 tonnes of gold between February and July 2024, bringing the Qatari central bank’s total monetary gold reserves to 108.8 tonnes.

However, there is more. Because while the QCB takes a few months to inform the IMF (and in turn the World Gold Council) of its most recent gold purchases, it actually publishes its reserves data very quickly on the QCB website in its official reserves statistics.

These statistics show that as of the end of September 2024, the QCB held exactly 3,559,766 ozs of gold, or 110.72 tonnes, which is 1.92 tonnes more than the July 2024 figure from the World Gold Council. So the Qataris have added 9.7 tonnes of gold so far in 2024.

Oman

The central bank of Oman nearly tripled it’s gold reserves over one month this year when it purchased 4.4 tonnes of gold in February 2024, bringing its total gold holdings to 6.7 tonnes.

Surprisingly, Oman, which is a member of the 6 nation Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) along with the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and Bahrain, had zero gold reserves until September 2022, at which point it purchased 1.86 tonnes, with some smaller additions in February and May 2023.

Sellers and Net Sellers during 2024

A quick word about some central banks which sold gold during 2024 and/or had sales in excess of purchasers (i.e. were net sellers).

The central bank of the Philippines, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), sold a substantial 27.9 tonnes of gold between January and July 2024. In September, the BSP released a statement on these sales saying that they were “part of its active management strategy of the country’s gold reserves” and that the bank “took advantage of the higher prices of gold in the market and generated additional income“.

But bizarrely, the BSP said that the the gold sales “did not compromise the primary objectives for holding gold, which are insurance and safety.” Which is bizarre, because selling gold (which is in a new bull market and is rising in value) is by definition compromising the primary objectives for holding gold. Its like selling the family silver at the beginning of a silver bull market,

After reporting purchases of 10.8 tonnes of gold between February and April 2024, Singapore’s central bank, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), sold 11.9 tonnes of gold during June, and sold another 1.33 tonnes during October, so was a net seller of gold year-to-date to the tune of 2.43 tonnes. After being one of the largest central bank gold buyers during 2023, the motivation of MAS for selling gold in 2024 is unclear.

Conclusion

With World Gold Council data on central bank gold buying being more than 75% comprised of estimates of ‘unreported buying’, it’s surprising that mainstream financial media outlets which quote that data verbatim, such as Reuters, Bloomberg and the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal, aren’t more vocal on pressuring the World Gold Council / Metals Focus to reveal just what kind of ‘market feedback’ and ‘confidential information’ they are basing their estimates on, and what the identities of these mystery buyers are.

As it stands, of the reported buyers, nearly all of them are emerging market economies and the vast majority span from Central Europe to the Middle East to Central Asia and right across to South and East Asia.

Some of the largest monetary gold buyers are BRICS founding members such as India and China, and probably still this year Russia. Other central bank buyers such as Turkey are now BRICS ‘partner members’. With BRICS announcing at the recent BRICS summit in Kazan that it plans to launch a BRICS precious metals exchange, it is clear that gold will play a role in any future BRICS monetary system.

The continued interest by central banks in accumulating gold as a reserve asset looks set to continue, and this has even been confirmed by the World Gold Council’s “2024 Central Bank Gold Reserves Survey” published in June which found that of 70 respondents, “29% of central banks respondents intend to increase their gold reserves in the next twelve months, the highest level we have observed since we began this survey in 2018.” If Q4 2024 central bank gold demand matches the fourth quarter of 2023 (which was 215 tonnes), this would bring full year 2024 central bank gold buying to more than 900 tonnes, which would be within shouting distance of the record years of 2022 and 2023.

That therefore seems that its ‘full steam ahead’ for central bank gold buying over the remaining months of 2024 and into the new year in 2025, solidifying gold’s role as a critical component of central bank reserve assets and signaling the ongoing ascent of the yellow metal to a starring role in any future global financial system.